Village of silk

After passing through a big brick gate built in the traditional style, I was quite impressed by the concreted road along which the air was filled with thousands of colourful umbrellas leading into Van Phuc Silk Village, which has been developed into a tourist destination in recent years, welcoming thousands of tourists a day.

|

|

Van Phuc is one of the most famous traditional craft villages in northern Vietnam. |

In a small snaking lane in the village, which is around 10 kilometres from the centre of Hanoi, six welders hunch to move a big silk dryer from the gate of a house to yard corner. Nguyen Thanh Minh, the owner of the house, says that his family has temporarily stopped producing silk for a couple of weeks to install the new dryers.

The power-run equipment will help Minh’s family dry silk more quickly. “I have spent VND270 million (11,740 USD) on three new dryers,” Minh says.

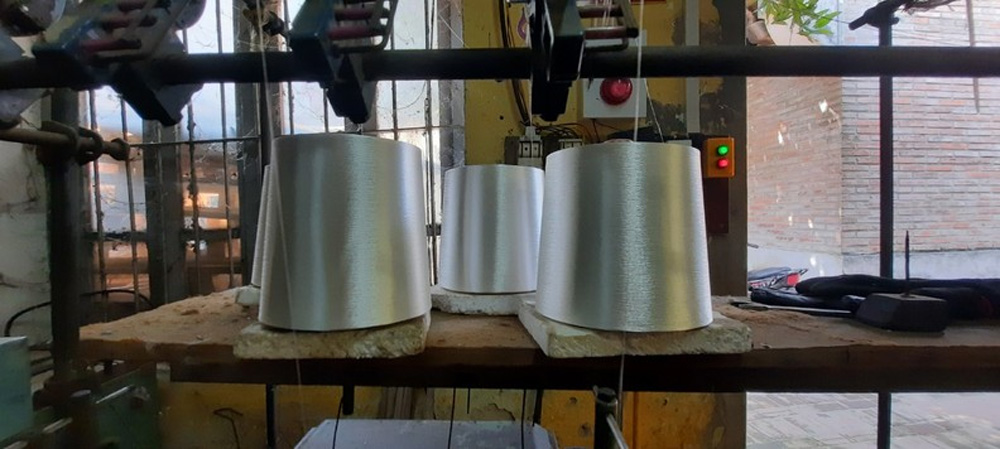

The dryers are about three metres high, with big metal tubes heated from inside. The tubes were covered by silk moving over around.

“All households in this village use powered dryers and weaving machines. It takes time to dry and weave silk manually,” Minh says while pointing to an old handloom in his kitchen corner. “We leave it as a keepsake!” he says.

About 10 years ago, when I first came to the village, I found silk waves which were drying in the sun, fluttering on the village’s rice fields and on the dyke of the Nhue River, which the village is located by. I could also find foreign tourists and painting students taking photos of such colourful waves.

He says silk could be dried when it was sunny, while with these dryers, it can be dried whenever in a very short time.

Home to about 800 households engaging in silk business, Van Phuc is a very famous silk producing village in Vietnam. It is reported that more than 700 years ago, silk weaving in Van Phuc was introduced by a woman coming from China’s Hangzhou City, which is globally famous for silk products. After years of accompanying her husband during his fights, the couple stopped at the village, where inhabitants were living in poverty without any craft. Then the woman taught the villagers how to weave silk.

However, another legend says that a princess of the Hung King royal family introduced silk making to the area nearly 2,000 years ago.

Another story also claims that about 1,200 years ago, La Thi Nuong, a girl from the northern province of Cao Bang, married a man in Van Phuc. Coming of a silk weaving family, she taught the villagers how to cultivate mulberry and raise silkworms and weave silk. After she died, she was given the title of Thanh Hoang Lang, or village genie.

|

Van Phuc silk was marketed in France’s Marseille and Paris international fairs in 1931 and 1938. It was highly appreciated by the French and is a favourite product in many nations in Europe.

At present, the village produces nearly three million square metres of silk on an annual basis. It boasts as many as 1,000 power weaving machines and more than 100 shops.

Traditional traits fading away

In Vietnam, silk is considered as the quintessence of Vietnamese identity for a long time since the reign of the sixth Hung King, started by Princess Thieu Hoa. Accordingly, silk was widely spread throughout the region from the plains to the mountains and highlands of Vietnam. From there, it formed traditional craft villages with a history of up to several hundred years. Over time, it has developed a deep national meaning.

I have learnt from books that Van Phuc produces silk from locally made materials, from mulberry cultivation to raising silkworms. The villagers have their own know-how regarding silk production.

|

However, in Van Phuc now, you can buy assorted silk of different origins, not only locally produced as you often hear about, because nearly half of the products in the shops here are foreign-imported or produced from imported materials.

“You will never find any family cultivating mulberry and raising silkworms now because of the narrowed cultivated land and a lack of human resources,” says Pham Minh Sinh, a silk weaver at her production workshop.

Pointing to a large and flat basket filled to the brim with dried silkworms, the 30-year-old craftswoman says the basket is used for decoration only and that when she began making silk about 12 years ago, the locals were not raising silkworms anymore.

Nguyen Thanh Nga, Sinh’s grandmother, invited me into her house cum shop which is packed with many types of silk and clothes – decorated with both traditional and modern patterns.

“We make silk materials ourselves but cannot meet demand for producing finished products. So, we have to buy more materials from China and some localities in the north,” Nga says.

She shows me products sold at many price levels, from VND20,000 (0.87 USD) to VND2-3 million (87-130.4 USD).

According to a number of shop owners, there are only about 10 samples of locally made silk because the households’ weaving machines produce the same samples.

“Meanwhile, there has been an increase in the number of shops. If we don’t sell import products with new patterns, our sales cannot go well,” says Nguyen Ngoc Thai, a shop owner.

It is costly and time-consuming to change a pattern because it relates to the change of the weaving machine structure, he says.

Earning a livelihood

After I have bought five shirts from his shop, I was told by an orange seller at the market nearby that only a small ratio of the shirts are real silk, and the remainder are made from nylon fibres.

“The imitated products cannot be discovered easily if you are not a connoisseur,” said the woman who sells me one kilogramme of orange.

|

She revealed that many shops sell almost imported goods, including all garments that can be found in an ordinary market. “That means Van Phuc silk is being attacked by foreign goods,” she says. “But that also means the life of local inhabitants has been improved significantly.”

Some foreigners enter a shop next to Thai’s. The saleswoman, like a pupil reciting a lesson, invites them in with some pidgin English: “Buy it, 100 percent real silk, traditionally made.”

I suddenly remember one year ago when my sister came here and bought a silk dress. However, the product turned out to be a Chinese-made one as she later found a “Made-in-China” mark on the fringe of the dress.

However, I was told that besides bargains, customers will likely be sold genuine products if they show an imperious look towards sellers.

While chatting with me, Jennie Pham, an overseas Vietnamese from the US, says she has learnt from the social media that Van Phuc produces and sells high quality silk produced manually.

“But, I can find even low quality silk here. What is more, many products are produced massively so they look the same,” says Pham, who is also a silk dealer.

“Why don’t local authorities tighten management over low quality products?” Linh wonders.

However, it is said widely here that no regulations about punishing those selling imitated goods are heard as shops need to “struggle to exist.”

According to many shop owners, most of the products produced here are sold domestically, only a small number of them is exported. In Hanoi, you can find Van Phuc real silk products in ancient streets, especially in Hang Gai and Hang Dao streets.

Source: NDO

Bắc giang

Bắc giang

Reader's comments (0)